As first post in my debugging series I want to introduce a way of visualizing software execution. This way you can see program state at a glance anywhere in time. If you have a clear mental picture of how a program executes, then it is much easier to find the root of your problem. Please note that I said mental picture. The diagrams created here are not for real-world use. Showing program state from beginning to end of any real program, would let the diagram explode to infinity. I will use these diagrams just as a vehicle for you to think about software and debugging strategies in later posts. Watching the Debugging course on Udacity by Andreas Zeller gave me the basic idea for these diagrams.

I looked around in what helped me in visualizing program execution and wanted something usable for any language and paradigm. Your mind is probably screaming, UML sequence diagram! Well, although a sequence diagram shows me the sequence of steps that is executed, it misses information about the values. You cannot see the internal state of the program at a certain point. You would have to read it from the source code, debugger or some kind of tracing.

So let’s go back to the drawing board. What do I want? I want a diagram that shows me the state of my software at all times during execution. But what is software?

What is software?

In software you always start with an initial state. For instance when you start your computer and freeze time at that moment, you could see all kinds of information. You could look at the values of all variables, settings, temperature, system load, free disk space and the contents of all files.

If you then unfreeze the time, and start some program, then stuff happens. Your computer transforms this initial input state into a new state. This stuff also known as software, is usually the program you’ve typed with great effort (or copy-pasted from StackOverflow). In the new state, most inputs still exist but have a different value.

If you would accurately record all the values at the initial state and would apply the exact same transformation, then the new state will be exactly the same.

So in software things happen for a ‘deterministic’ reason, because a program consists of:

- finite set of inputs: Such as input by users, files, hardware effects, system load, etc..

- finite set of transformations: Methods, functions, calls, etc…

- finite set of outputs: files, print to screen/console, action on port, etc…

So we should accept that:

Software isn’t magic.

Making a diagram

So lets put this information to work for us and start constructing our visualization using these inputs, transformations and outputs.

If we draw a set of blocks in a row, each representing an input element, we can show the initial state.

Each block can represent any kind of input, such as files, environment variables, port, memory locations, etc.

Say we have some python code in which num1 and num2 have some initial value.

1

num1, num2 = 3, 5

Now we have some inputs, having some initial state is nice, but off course worth nothing if we don’t do anything with it.

Let’s add a transformation which changes this state into a next state.

Notice how max_num has no value at the first line. Lets mark this with a ‘?’.

1

2

num1, num2 = 3, 5

max_num = 0

So, now we are done, aren’t we? We have the inputs, transformations and outputs you mentioned.

Nope, not quite, although this graphic can represent simple linear programs.

How about statements that influence the flow of a program?

If you have an if statement the outcome of the if statement should somehow be represented.

The state of the software will be different when it evaluates to True or False.

What if we just add line_number as input.

Think of it as the program counter keeping track of where we are in the program.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

num1, num2 = 3, 5

max_num = 0

if num1 > num2:

max_num = num1

else

max_num = num2

So, now we are really done. Aren’t we? Nope, we can now represent any function or method. But off course any proper program has more than just the main function or module. So we should add a way to represent this. Lets add a dotted line to represent switching a context frame. Each frame represents a different scope, so local variables are not visible anymore when you cross this. To represent this non-visibility (actually non-existence), lets mark them with an ‘X’.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

def find_max(num1, num2):

max_num = 0

if num1 > num2:

max_num = num1

else

max_num = num2

return max_num

my_max = find_max(3, 5)

You could extend this diagram model even further for multithreading and non-blocking call stuff, but that is food for another post. It will otherwise clutter your mind a little bit too much for now.

Dependency chain

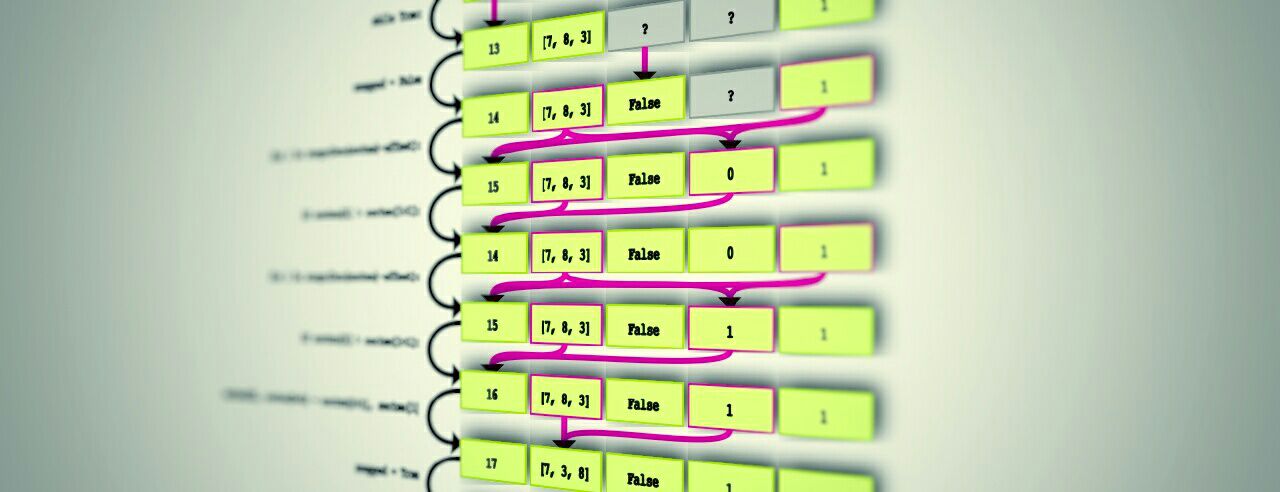

So we now have a way of representing the state of a program during each step. But what if we want to know what influences what? If we want to get any useful information out of this we should somehow visualize parts that influence eachother. Lets link up the input values of a transformation to the output values of a transformation using an arrow.

If we now apply this across the entire figure, we get a chain of dependencies. This is appropriately called a dependency chain. A dependency chain is great for visualizing what your software does and how each step interacts. These are also referred to as program slices. These will be a key concept for my future debugging posts.

Creating these diagrams

You must be thinking by yourself:

OK, but I’m not going to draw these diagrams by hand. I have better things to do!

Off course you shouldn’t! I created a little python script that can generate these images from python with trace information.

It is currently in a proof-of-concept stage, so please be gentle on me ![]() .

It should be do-able to extend the tool to c using gdb, but that is on my looooooooong to-do list.

Head over to the PrintState repo and check it out.

.

It should be do-able to extend the tool to c using gdb, but that is on my looooooooong to-do list.

Head over to the PrintState repo and check it out.

Further reading

- Other visualization techniques

- Visualization technique overview by RUG

- These diagrams were inspired by the Debugging Udacity Course of Andreas Zeller